The Christian Faith, Native Religious Traditions & Society:

In the first and second centuries AD, the Christian faith spread very widely among the the poor and the slaves, to whom Christ’s teaching offered new hope and comfort. Excellent new communications by land and sea, and the movement of Roman troops, assisted the spread of the faith across all parts of the vast empire. Churches were organised and supervised by bishops, or ’elders’. Christians were, however, persecuted by successive Roman emperors because they refused to put their duty to the State before their devotion to the ’One God’. Since they were so loyal to their beliefs and showed such courage under persecution, these early Christians gained respect for their faith and their numbers grew. By the year AD 140, all the original disciples, apostles, and all those who had been associated with them were long-since deceased; the last of them probably being the children of Pudens and Claudia, whom Paul referred to at the end of II Timothy (4 v. 20).

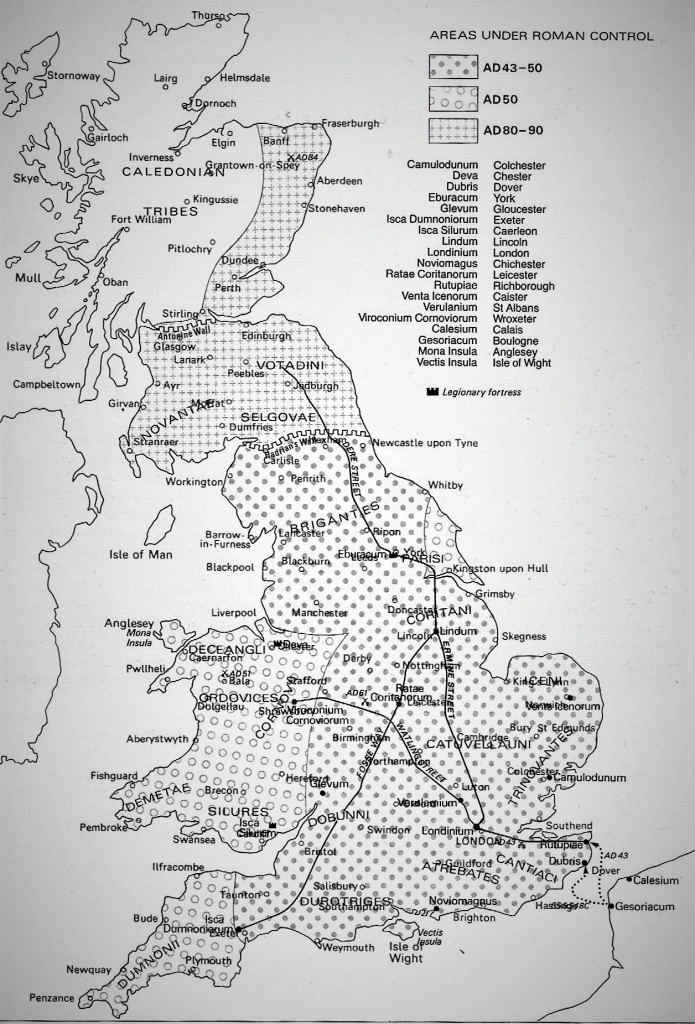

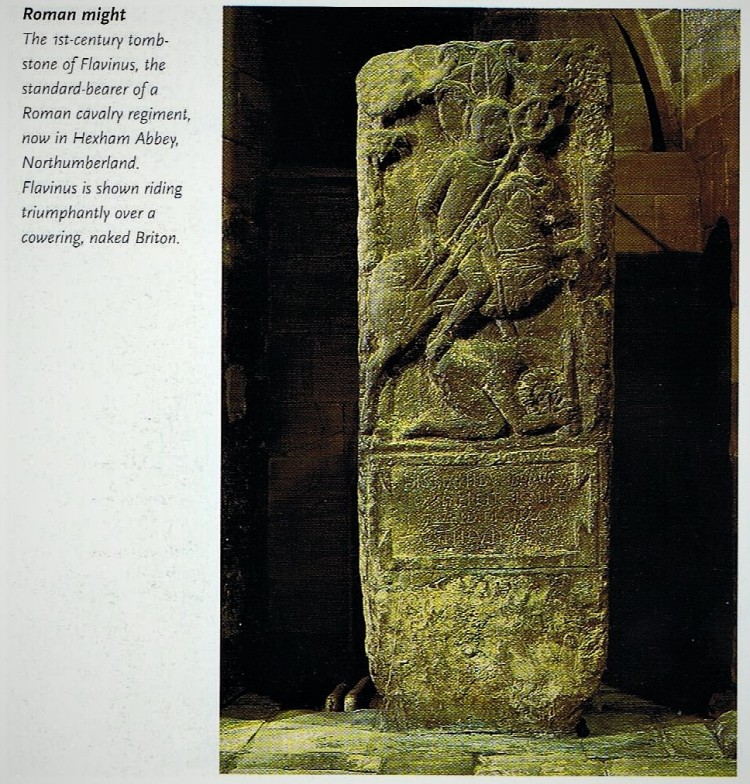

A few of them, perhaps including Paul, had fulfilled the command to go to all corners of the known world, both east and west, preaching the Gospel. It is difficult to believe that this handful of men and perhaps women could have achieved such a formidable missionary enterprise within little more than thirty years of Jesus’ death, but there is sufficient evidence in the New Testament, apocryphal and early church sources to believe that they did, leaving aside the more obvious myths and legends. For the second and third generations of Christians, the task of spreading their faith to the various native populations of the Roman empire was still fraught with danger. This was especially the case in Britain, where, after the initial conquest carried out by AD 83, the missionaries lacked either the protection of friendly tribes or that of sympathetic governors against tribes who were still hostile to both armies and missionaries from Rome and determined to continue worshipping their own gods rather than the Christian one. For another century and a half, until the time of Constantine, Christianity remained a minority, often persecuted religion in the province, as in the empire as a whole.

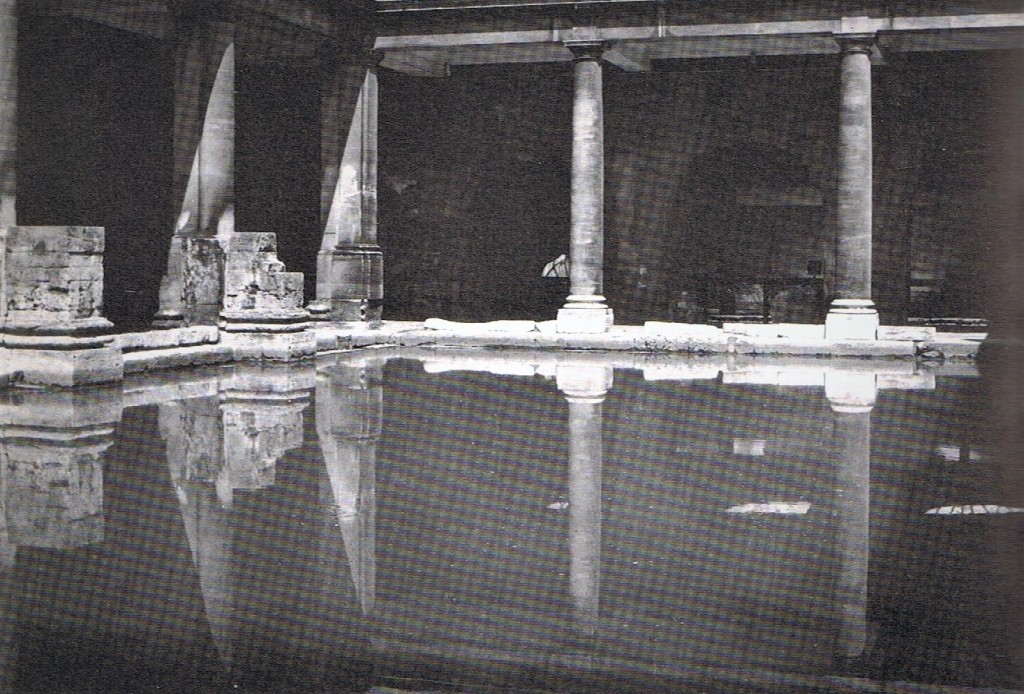

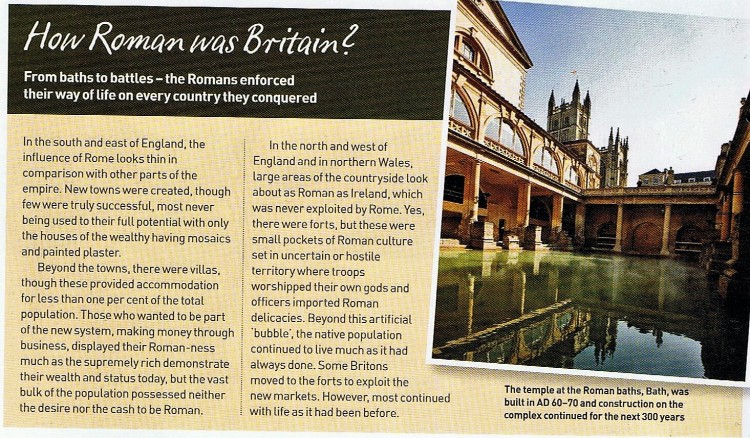

In fact, the conquerors were far more tolerant of the native religion of the Celts once they had destroyed the power of the Druids. As long as the due rites had been paid to the gods of the state, including tribute to the god-emperor, the Romans had a remarkably ecumenical attitude to religion. The toleration of native cults eventually led to a fusion of beliefs which appears in the style and flavour of the best Romano-British art, most notably at Bath. The hot springs of Bath had been under the care of a Celtic goddess, Sul. The Romans, from an early stage of their occupation, used Bath, or Aquae Sulis as they called it, as a convalescent centre for sick legionaries. Around the sacred spring of Sul, now beneath the later King’s bath, grew up a resplendent series of buildings connected either with worship or with healing or with both. They identified Sul with Minerva and built a magnificent classical temple to this composite goddess.

The resilience of the native religious traditions is shown not only at Bath but right throughout Britain in the whole period of Roman occupation. At Lydney in Gloucestershire in the latter years of the fourth century a temple complex was built to the Celtic god Nodens, a god of hunting and the sea who was also regarded as a powerful healer. The temple was set beside a guest-house and a building where the patients and suppliants probably spent the night in the hope of a dream or a visitation from the Greek god of healing, Aescapulius. Egyptian practices in which sleep and dreams were considered of the greatest therapeutic nature, part of a multi-cultural pagan religious mix.

Unlike Bath, most Romano-British towns have survived or been resettled so successfully that it is difficult to capture their original sacred nature. It suited Rome to rely on local leaders for local administration; as in Rome itself, such responsibility fell to the wealthy, as they were expected to contribute personal wealth as well as effort. The pre-Roman tribal leaders and their descendants became the core of the new administrative system. The Romanised tribes (civitates) did not necessarily correspond precisely in territorial terms with their predecessors, but they provided an important element of continuity. Within these territories, sites were chosen for towns to act as the administrative centre. These were the successors of tribal meeting-places, though they did not usually occupy the same sites. They were more likely to be built on lower ground, and often developed from vici that had appeared early in the Roman occupation – and so were closely integrated into the system of communications. Corinium (Cirencester), for example, established on the site of an early fort, succeeded in the tribal centre of Bagendon as the administrative centre of the Romanised Dobunni, and became one of the most thriving towns of Roman Britain. Interestingly, Corinium generated a greater level of social and commercial activity than nearby Glevum (Gloucester), one of a number of colonia or settlements created for legionary veterans. Corinium’s success is a measure of the opportunities – commercial, agricultural and industrial – available to Romanised Britons.

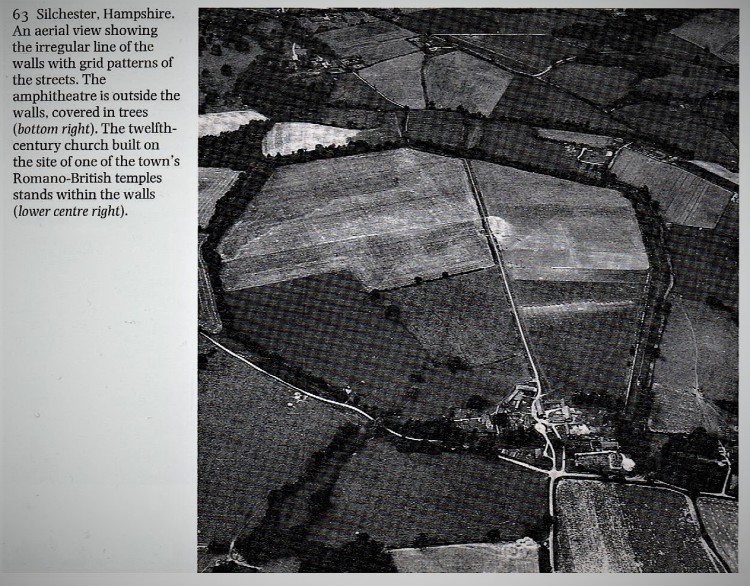

The social and political rewards available to those who took on administrative responsibilities must have been considerable, for the financial burden was substantial: they had to pay for building and repair work in the towns, for local religious and secular ceremonials, and even for shortfalls in local tax payments – or be prepared to raise loans to cover these. A particularly heavy expense in the later years of Roman Britain arose from the walling of towns. The towns of Roman Britain may not have enjoyed the magnificence of those in other parts of the empire, but they certainly had similar facilities: a forum (public square), baths, temples and places of entertainment. They were also places of work, and much industrial raw material and agricultural produce was taken into towns to be processed into saleable items. Such towns, both large and small, were places of noise and bustle. The links between urban and rural life were strong, especially since many of those who administered the civitates made their money from industries whose raw materials came from the local countryside, or from local agriculture; records on writing tablets from Vindolanda on Hadrian’s Wall provide evidence of this. The small scale of the abandoned town of Silchester, revealed in the aerial photograph below, shows that although the south-east became the most urbanised area of Britain, British towns remained small compared to those on the Continent.

Silchester is one of the few Romano-British towns that never regained their status after the Dark Ages. It was the tribal centre of the Atrobates and the Romans called it Calleva Atrebatum. Although there have been several excavations there and many important discoveries, both of buildings and of artefacts, have been made on the site, nothing remains above ground except long expanses of the walls and an amphitheatre outside the town. The stone facing has long been ripped away from the walls so what one walks beside is a long, rugged cliff of large flints embedded in mortar, strengthened with courses of flat sandstone. The isolation of the place, in the north Hampshire countryside, and the lack of any buildings except a farm and an old church built on or close to the site of one of the Romano-British temples at the edge of the walls concentrate the mind upon the significance of the changes brought about by the Roman invasion. Aerial photographs show clearly, together with other reconstructions in the Silchester museum, the grid system on which the first Romano-British towns were laid out, following the Etruscan pattern. The temples suggest a fusion of Celtic and Roman beliefs. Also beneath the soil lie the remains of an early Christian church, said to be the earliest north of the Alps. Silchester also appears in the later Arthurian legends as the town where Arthur was crowned, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth.

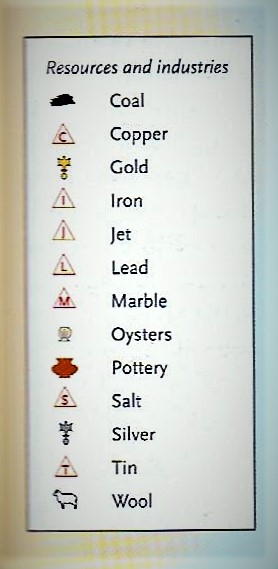

As the map above shows, Roman Britain was divided into two broad social and economic zones. In the fertile lowlands of the south and east a prosperous agricultural economy developed based on villas. Culturally, this area became the most Romanised area of the province. Rural settlement patterns varied between the lowland and highland areas of Roman Britain. In the lowland areas south and east of a line from the Humber to the Severn, villas were a major feature of the landscape. These ranged from small, rectangular cottages to large country houses, according to the resources of their owners. Most were built on the profits of arable estates or stock-rearing. To the north and west of this line, there were few villa estates, so that these areas were valued as much for their mineral resources as for their agriculture. Both farming and settlement here showed greater continuity with Celtic pre-Roman practices.

Circular and rectilinear huts were more frequent in the upland areas of the West Country, while in northern ‘Cambria’, the Pennines and the Southern Uplands of Caledonia no remains of villas have been found at all. There, rural settlements consisted entirely of native people and retired soldiers. Unprepossessing as their huts and farm buildings may seem, the economic opportunities they offered were no less significant than those of their richer counterparts in the south and east. Some civitates in northern Britain – for example, the Brigantes and the Carvetii – grew considerably under Roman rule.

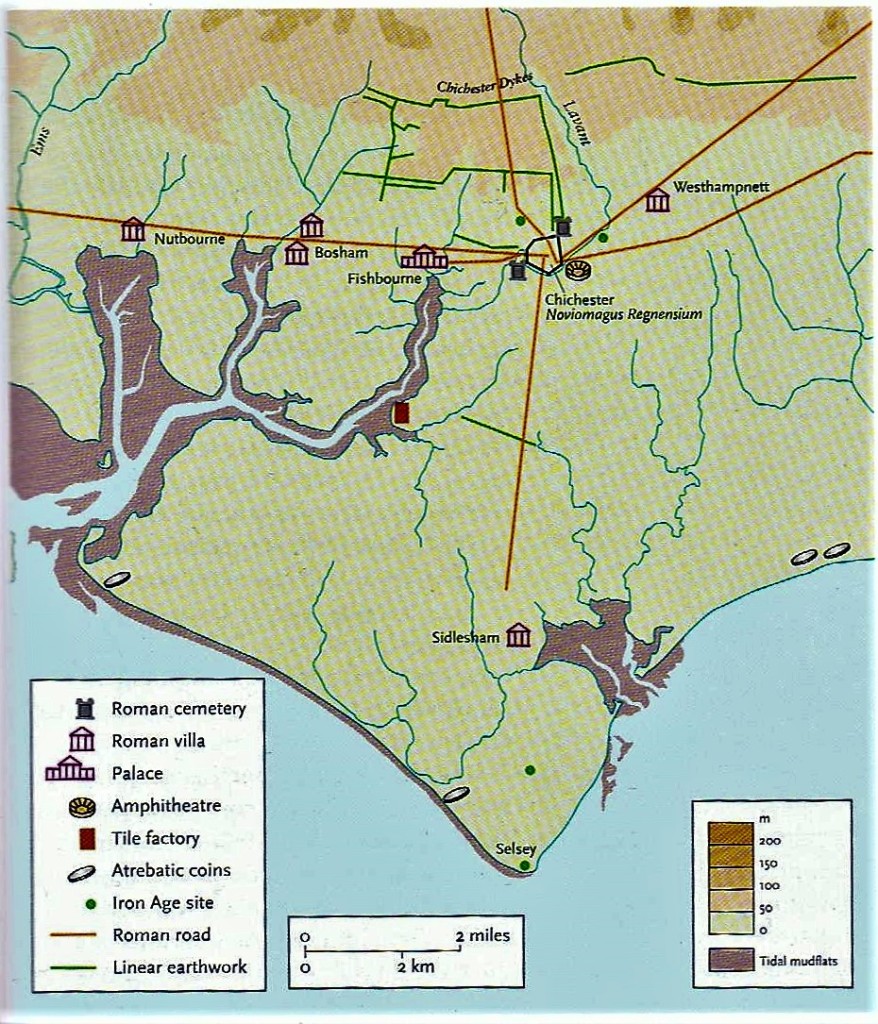

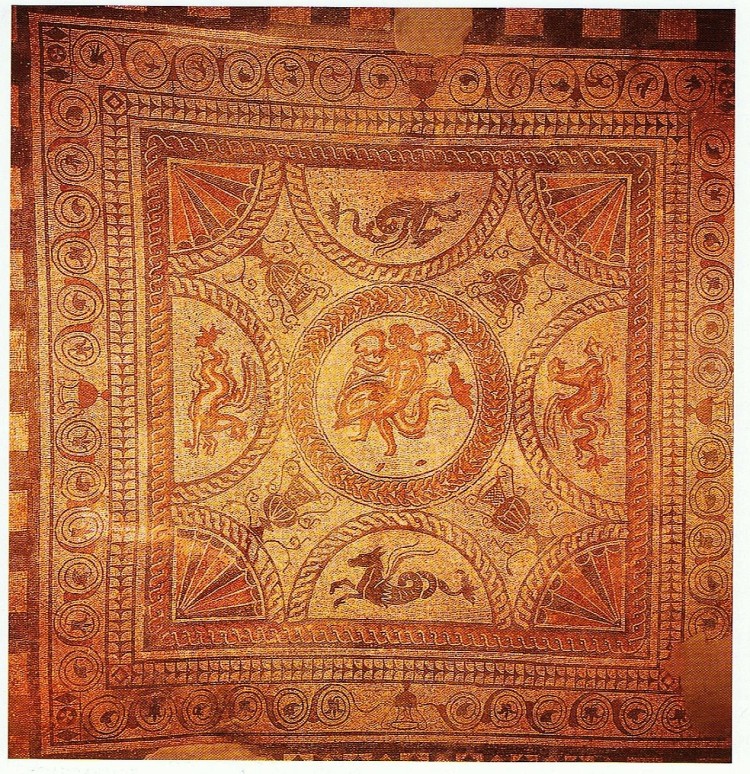

Although the Romans rated military glory highly, conquest had never been an end in itself. If a province was to be fully integrated into the empire, the willing cooperation of its people had to be guaranteed through a process of Romanisation. In Britain as elsewhere, conquest created the conditions in which this transformation could be achieved. This process has been demonstrated by archaeological evidence from chance discoveries around the city of Noviomagus Regnensium (Chichester), the tribal capital of the Atrebates (Regnenses) which have not only revealed a major palace site at Fishbourne but have also provided an insight into Rome’s policies towards the British ruling classes in the earliest days of the invasion. The Artebates had a long history of good relations with Rome and readiness to trade with the Roman empire: the tribal leader, Verica, was a client of Rome whose discomfiture at the hands of Caractacus had provided one of the reasons for the Roman invasion. The attitude of the Atrebatic leaders explains why their territory provided a secure base for the Roman army; pro-Roman sentiment is also hinted at in dedication to the Roman gods Neptune and Minerva made by the obviously privileged local leader, Cogidubnus. His pre-Roman centre was at nearby Selsey, and he appears to have been left in charge of a semi-independent portion of the Atrebates with the descriptive name Regnensis (‘people of the kingdom’ – that is, self-governing, rather than under direct Roman rule). In Nero’s reign (54-68), the military buildings at Fishbourne were updated to what has been called a proto-palace. In about 75, this was in its turn replaced by a palatial villa constructed around a garden courtyard, and well-appointed internally with mosaics, wall paintings and statuary of Mediterranean origin. The villa retained its high status well into the second century, probably belonging to the local client king or a senior Roman official.

The Romano-British, the Roman Army & the Frontier:

The traditional view of the Britons as sullen opponents of Rome over four centuries has to be abandoned, therefore. The Romano-British benefited from a range of economic and social opportunities offered by the Roman occupation. This was made possible by the treaties secured first by Agricola and then by Hadrian. Tacitus states that from AD 43 to AD 86, sixty major battles were fought on British soil, but the following thirty years saw a period of relative peace in which the only fighting was on the Caledonian frontiers.

The original intention of the Roman commanders had been to delay the conquest of the North until the Midland tribes were subdued; the treaty with Cartimandua had been intended to make this possible. After Caractacus’s capture, however, her position among the Brigantes proved less than secure, not least because of anti-Roman sentiment stirred up by her own husband, Venutius. The rivalry between them forced Rome’s hand: Roman military and naval forces began to intervene in the North in the fifties and sixties, operating from bases such as Viroconium (Wroxeter) and Deva (Chester). Rome’s difficulties in the North came to a head in 69, when Venutius took control of the Brigantes; Roman forces had to rescue Cartimandua from her stronghold, a hill-fort at modern Barwick-in-Elmet. The Roman response to Venutius’ coup was severely hampered by the upheavals of the ‘Year of the Five Emperors (68-9), an empire-wide political and military struggle between the rival successors to Nero in which the British legions were involved. The eventual victor was Vespasian, who established the Flavian dynasty, which ruled from 69 to 96 AD. Vespasian was determined to renew the programme of conquest in Britain, evidently intending to bring the whole of mainland Britain into the Roman province. Venutius was dealt with by the governor, Marcus Vettius Bolanus, who thereby laid the foundations for substantial territorial gains under Quintius Petillius Cerialis (71-74) who, in the north, advanced into the territory of the Brigantes. Under Julius Frontinus (74-8) the scene of military activity then moved to Cambria where his defeat of the Silures and the Ordovices was later consolidated by Agricola in a swift campaign which ended in the capture of Anglesey.

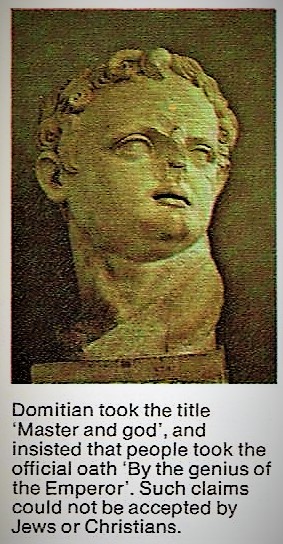

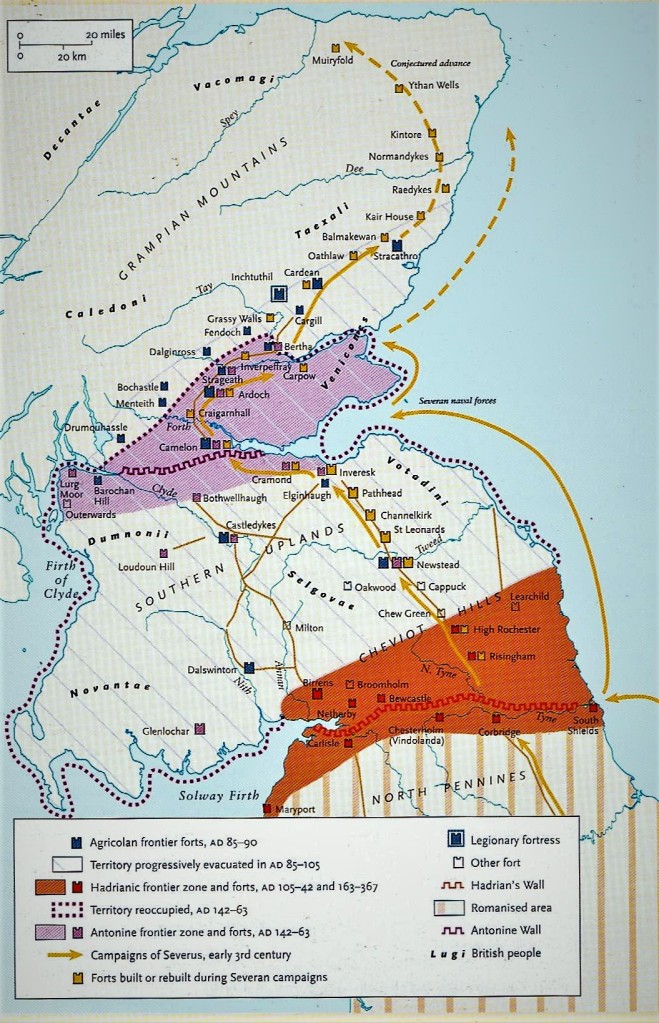

As governor, Agricola (77-83) then turned to the north where he planned to build upon the defeat of the Brigantes by the expansion of Roman control to Chester in the West and York in the East. Cerialis probably secured most of the territory up to Luguvalium (Carlisle) and Coriosopitum (Corbridge), establishing a legionary fortress at Eburacum (York). In Caledonia, Cerialis cultivated the Votadini, whose grain was of value to Rome, as a Roman client. He also separated the Venicones of Fifeshire from the Caledonian hillspeople by a line of forts and watchtowers now known as the Gask Ridge limites. Between 79 and 81, Agricola pushed forwards with legionary columns from Chester and York. He reached the line of the Forth-Clyde isthmus and then pushed on to the Tay estuary, establishing forts to consolidate the ground won. Agricola’s governorship is well recorded, thanks to a biography written by Tacitus, his son-in-law. However, the chief author of policy in any province was the emperor; during Agricola’s governorship, three different men held this position: Vespasian (until mid-79), Titus (until late 83) and Domitian (83-96). Vespasian favoured total conquest, while Titus was more circumspect, perhaps preoccupied with unfolding problems on the Danube which led to the removal of legionary troops from Britain in AD 80.

Until the early 80s AD, total conquest was the Roman goal in Britain. The frontiers (limites) were merely zones around fortified roads that temporarily seperated friendly tribes from enemies. In the summer of 83, Agricola planned to bring the Caledonian tribes to battle, even though his own command had been reduced by the transfer of both legionaries and auxiliaries to the defence of the Rhine frontier. Domitian permitted a resumption of the colonial advance, but perhaps with the limited objective of reducing the fighting power of the Caledonians, in case further troop withdrawals should prove necessary. Agricola advanced with his troops in an attempt to encircle the Highland massif, building forts to block the exits provided by the glens. His campaign camps suggest that he provoked the battle by denying the Caledonians access to the coastal lowlands to their east and northeast, just as the Gask Ridge forts had blocked the glens through which they could reach the lowlands to their southeast. A serious reverse befell the IXth Legion when a Caledonian force broke into the legion’s camp during a night attack. The situation was only restored by the arrival of Agricola with reinforcements.

Agricola may have had personal misgivings about Domitian’s policy, but did his duty: at the battle of Mons Graupius in 83, he effectively committed genocide on the Caledonians. Determined to restore the security of their Highland refuge, the Caledonian tribes assembled their greatest strength and confidently awaited Agricola’s approach at Mons Graupius. A tribal army of thirty thousand under its leader Calgacus confronted a Roman force of roughly equal strength. Agricola kept the IXth and XXth legions in reserve, forming his main battle line from eight thousand auxiliary infantry and five thousand auxiliary cavalry. Since the Caledonians occupied the high ground and their position was screened by a line of chariots, Agricola launched his cavalry against the charioteers while his infantry engaged in an exchange of missiles with the enemy. When the charioteers began to give ground, Agricola advanced with his Batavian and Tungrian infantry to bring the tribesmen to hand-to-hand conflict.

As the auxiliaries drove into the Caledonian line, the mass of tribesmen to the rear began to move forward, down the slope, overlapping the Roman flank. Agricola halted this threat with a charge by auxiliary cavalry which broke through the opposing line and wheeled round to take the enemy infantry in the rear. As the cavalry broke into their ranks, the tribesmen turned and fled, leaving ten thousand dead on the battlefield. According to Tacitus, the Roman loss was 360 auxiliaries. It was a remarkable outcome, particularly as it had been achieved solely by auxiliaries, but it was not the victory for which Agricola had hoped. Over two-thirds of the Caledonian army had escaped leaving the tribes with sufficient strength to threaten the northern border of the province. The site of Mons Graupius has still not been conclusively identified but the location of a large Roman camp near Inverurie to the north-west of Aberdeen suggests that the mountain known today as Bennachie, 1733 feet (528 metres) could be Mons Graupius. It appears that Agricola continued his advance to the shores of Moray, and even to modern Inverness: recent excavations have revealed camps at Thomshill and Cawdor.

Agricola had seen his victory at Mons Graupius as an opportunity to complete the conquest, but the emperor Domitian, with responsibility for the whole empire, had to reflect more circumspectly. Recognising the futility of the strife and the decimation of its legions from the forty-year war, Rome had found her military defence so weakened that she was hard put to defend her own frontiers elsewhere. Agricola, who had experienced the mettle of the British on many a battlefield, was more broadminded than any of his predecessors. He was convinced that the Britons were oblivious to persecution and war. Like Julius Caesar, he realised that neither defeat nor privation would discourage their warriors. He effected a more humane policy by inaugurating a treaty that incorporated the tribes as allies in the empire, recognising all their native freedoms and kingly prerogatives. He was recalled to Rome in AD 83; despite the suggestions of Tacitus, there appears to be nothing sinister in this, as his tenure had already been extended to twice the norm. His departure did not coincide with a Roman plan to abandon Caledonia. Indeed, it is likely that the building of a new legionary fortress at Inchtuthil is attributable to his unknown successor as governor. Such a commitment implies an intention to remain in the area for some time.

The Roman Advance Halted – Two Treaties & Two Walls:

By neutralising the last remaining enemy tribes in the British Isles, Agricola’s victory at Mons Grapius made it possible for Rome to halt its territorial expansion within Britain at a time when frontier problems in Europe were mounting. Britain could no longer take priority over these problems. The period of the conquest was over; that of occupation and consolidation took over. With the empire under pressure on the Danube, Domitian began to withdraw troops from Britain. By 87 the building of the new fortress had been abandoned, and one of the four British legions in Britain, Legio II Adiutrix, was in the process of transferring to the Continent.

By the end of the first century AD, Roman expansion in Britain had come to a halt. The territory won by Agricola beyond the Forth-Clyde line was therefore abandoned. The essential pattern of the Roman Conquest in Britain had been set, and thereafter the central, south-eastern and the south-western areas of the province enjoyed two hundred years of comparitive tranquility. The north and to a great extent the west remained militarised zones, constantly garrisoned and patrolled. Normally the garrison of Britannia was a strong one, comprising in the region of fifty thousand men, but at times of crisis in the empire its strength would be depleted by the transfer of troops to deal with whatever emergencies had arisen. The inevitable consequence was a resurgence of conflict on the under-guarded northern and north-western frontiers. Raiders, whether Picts, Scots or Saxons, could wreak considerable havoc, attacking forts and looting settlements. Once the wider emergency had been settled to Rome’s satisfaction, retribution followed, often in the form of an imperial task force which restored order by burning tribal strongholds, destroying livestock and crops, and building yet more forts. It was when Rome could no longer deliver such retribution that imperial rule in Britain began to falter.

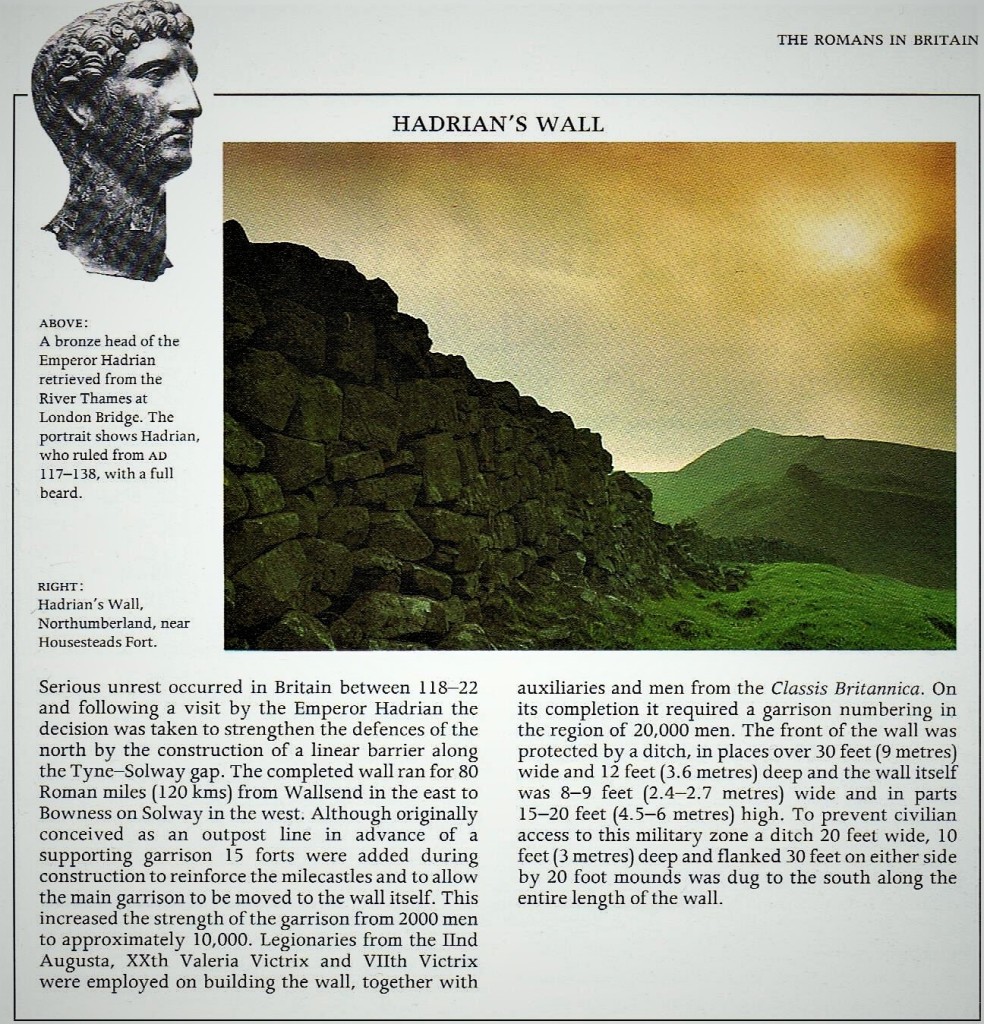

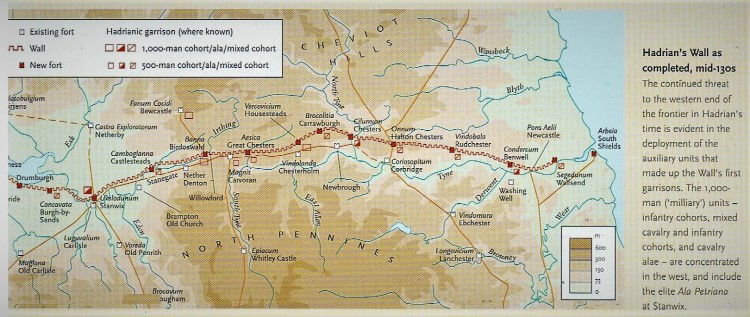

The last forts north of the Forth-Clyde line were evacuated around 103, as the legions formed a new frontier zone around the road now known as Stanegate. Over the next twenty years, the Roman legions in the north progressively withdrew from the southern uplands, occupying a zone between the Cheviot Hills and the Tyne-Solway line (as shown on the map above). To deter raids from the north the forts along this military road were refurbished and additional posts built. This frontier eventually ran from Arbeia (South Shields) to Kirkbride, and consisted of the road itself, strengthened by a palisade and ditch, and forts, such as Vindolanda, fortlets and watchtowers. Our knowledge of this period is limited, but it seems that on the accession of emperor Hadrian in 117, the western end of the Stanegate was under threat from the tribes to its north. Serious fighting occurred broke out in 118, but by 119, stability on the northern frontier had been restored, and it was probably then that the Romans began work on a turf wall from the Ituna (Irthing) to Maia (Bowness).

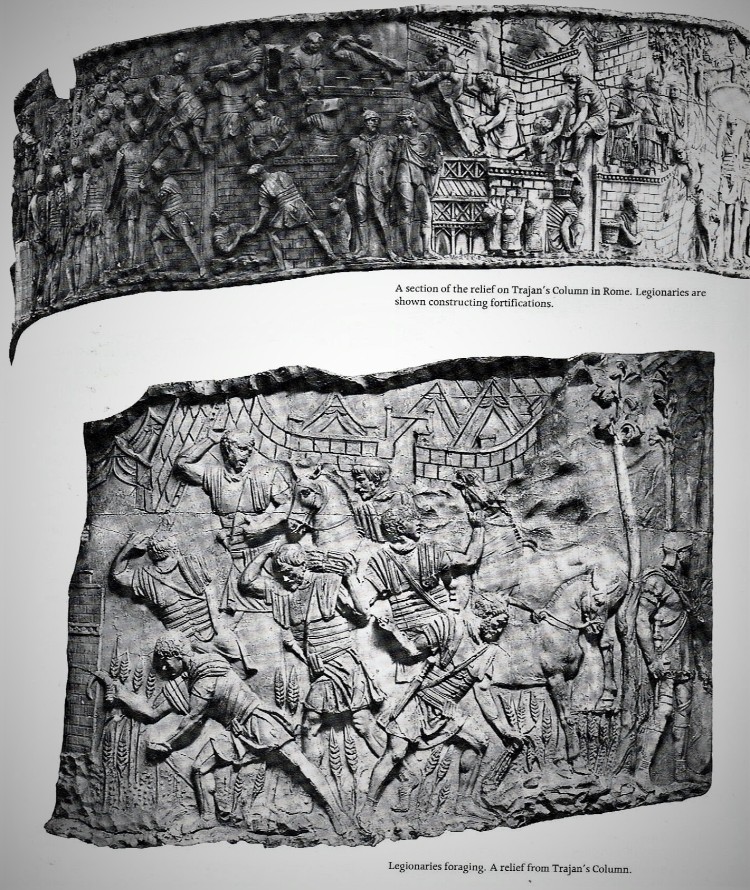

In AD 120, Hadrian developed the terms of Agricola’s treaty, which had merely permitted the Romans to hold certain military bases in Britain. The two treaties taken together eventually helped to create the long peace between Rome and Britain that lasted up until the Diocletian persecution of circa AD 300. In 122, following a renewal of fighting, however, Hadrian himself visited Britain with a new plan: to construct a stone wall from Pons Aelii (Newcastle) to join the turf wall at Willowford. During his visit, he decided that his policy of replacing his predecessor, Trajan’s stance of imperial expansion with one of retrenchment would be extended to Rome’s northernmost frontier. Trajan’s policy is best demonstrated in his ‘Column’, sections of which are shown below.

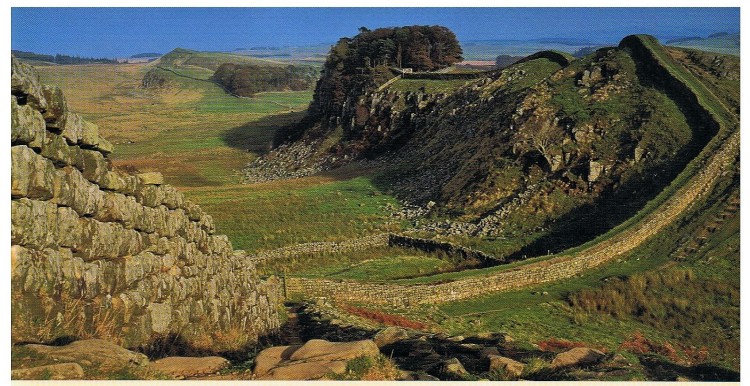

This stone wall, which occupied the ridge to the north of the Stanegate, was intended to enhance the former frontier but actually superseded it, eventually becoming a much more elaborate military complex. In its final form, it consisted of a ditch to the north, the wall itself with forts, mile-castles and watchtowers along it, and a military road with a vallum (embanked ditch) to the south. Territory to the north was supervised, creating a substantial frontier zone. By the time of Hadrian’s death in 138, the turf wall had been rebuilt in stone, and the fortifications extended along the coast to Alauna (Maryport). The purpose of these structures was given at the time as ‘to separate the barbarians from the Romans’. They were certainly intended to facilitate the supervision of movement across the frontier and the collection of taxes from the crossing. Additionally, they allowed patrolling and other forms of intelligence gathering. The wall’s construction in stone also suggests that it was intended to provide a demonstration of Roman organisation and technology, and to serve as a monument to an emperor who well understood the connection between buildings and political power.

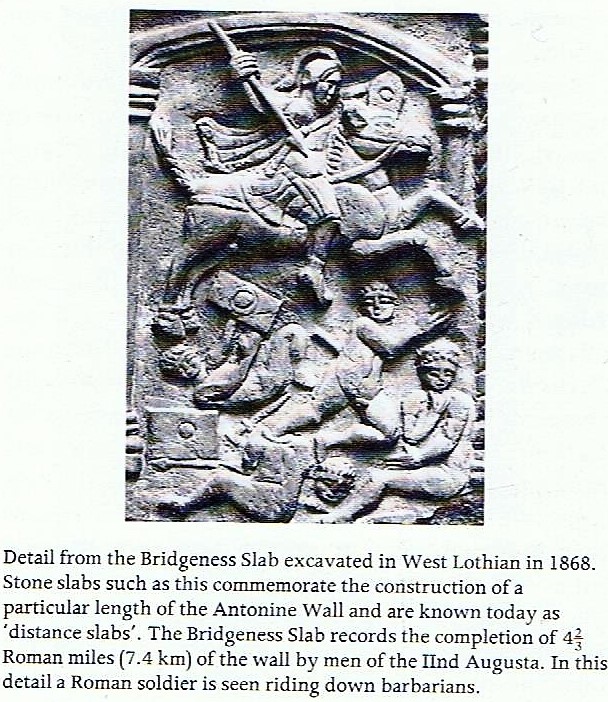

The new emperor, Antonius Pius, following his accession in 138, decided to abandon Hadrian’s Wall and to reoccupy lowland Caledonia, territory up to a line from the river Clota estuary to the Bodotria estuary (the Forth-Clyde isthmus) and around 140 he commissioned the construction there of a new wall, a hundred miles to the north of Hadrian’s Wall. This was built throughout of turf, though there are signs that a stone construction was originally anticipated and it was probably intended to resemble Hadrian’s Wall in form. The Antonine Wall, as it became known, was thirty-seven miles long, subsequently modified in favour of a design with forts of varying size at much shorter intervals. Little is known of what precipitated the advance, although the fact that disturbances continued intermittently through the second century among some of the tribes between the walls suggests that the objective may have been closer policing of these tribes. It acted as the frontier for some twenty years before Hadrian’s Wall was recommissioned. Similarly uncertain is the explanation for the apparent break in the reoccupation of the southern uplands in the mid-150s, but the emperor Marcus Aurelius decided in 163 to permanently abandon the Antonine frontier zone and reoccuppy Hadrian’s Wall.

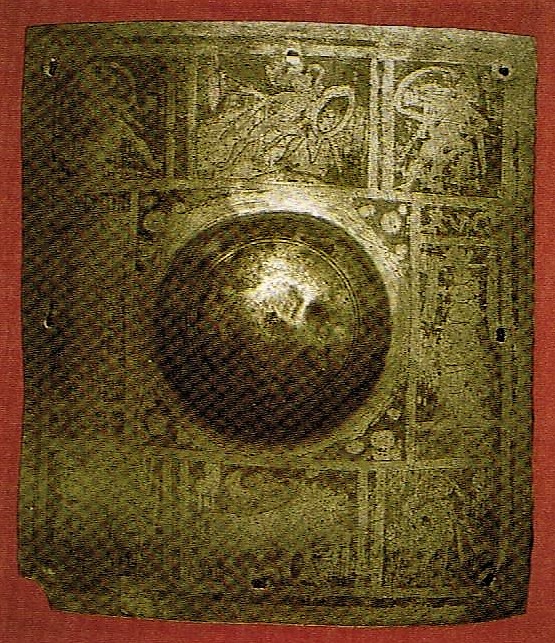

After 163, therefore, the permanent frontier line ran from the Segedunum (Wallsend) on the Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west, providing along the Wall’s eighty (Roman) mile course. This was now a stone construction along its entire length, with a series of forts built alongside it to house the fortification’s garrison. The five listed on the Rudge Cup – Mais (Bowness-on-Solway); Aballsva (Burgh-by-Sands); Uxelodunum (Stanwix); Camboglans (Castlesteads); Banna (Birdoswald) – held units of auxiliaries, non-citizen soldiers, of whom some thirty to thirty-five thousand supplemented the fifteen thousand men of the three legions based at York, Chester and Caerleon.

The forts along Hadrian’s Wall were punctuated by milecastles and turrets, smaller fortifications which held detachments from the main units. The role of this garrison was probably a deterrent and supervisory one, monitoring movements among the tribes to the north of the Wall, controlling passage south and in the main area of Roman Britain and , exacting tolls from those who passed through its gates and handling any small-scale incursions. Any larger breaches or invasions would be dealt with by pulling troops back from the Wall and by II Augusta Legion based in York. Periodically emperors embarked on punitive expeditions to the north, such as Septimus Severus who arrived in Britain in 208 to restore order to the frontier. Up to that point, continuing tensions in the frontier zone had been handled with a combination of military force, diplomacy and subsidies. In that year, Septimus Severus, from bases at Coriosopitum (Corbridge) and Arbeia (South Shields), led a new and well-organised combined military and naval advance into northern Caledonia, perhaps with genocide as his aim. But he was to die at York. A successful campaign, though apparently without pitched battles, followed up by intense diplomacy, finally brought a stability to the northern frontier which was to hold for more than a century.

Thereafter, Hadrian’s Wall remained the principal fortified line for another two hundred years until its abandonment in 409. The northern tribes are recorded as having breached it on several occasions, most notably in 367 when a ‘barbarian conspiracy’ of Picts, Scots and Irish almost overran the province before being thrown back by Count Theodosius, a special military envoy dispatched by the Emperor Valentinian. In the west and the east the province came under attack by seaborne raiders. From Ireland, which the Romans had never attempted to conquer, raids were launched against the west coast of Britain, and coastal forts such as Cardiff (Caerdydd) and Lancaster were enlarged or reconstructed in such a way as to give protection from the sea. By the end of the second century, Saxons were already raiding the south-east coast and the erection of forts at Brancaster and Reculver in the early third century was the beginning of a major coastal defence system. The series of fortifications from the Wash to Southampton Water which became known as the Saxon Shore, denied the raiders entry to the river estuaries which could carry them inland. The forts served as as a base from which garrisons could contest Saxon landings, and ships of the Classis Britannia could attempt to meet the enemy at sea.

Lleurug Mawr (Lucius)/ The ‘Great Luminary’ of the Britons:

The first mission to Britain for which we have any detailed evidence was, apparently, one sent by ‘Pope’ Eleutherius (died 24 May 189), also known as Eleutherus, who was the thirteenth bishop of the Roman Church from c. 174 to his death (The Vatican cites 171 or 177 to 185 or 193.) He is linked to several legends, one of which credited him with receiving a letter from “Lucius, King of Britain” or “King of the Britons”, declaring an intention to convert to Christianity. No earlier accounts of this mission have been found and the account of the letter is now generally considered to be a pious forgery, although there remains disagreement over its original purpose. Haddan, Stubbs, and Wilkins considered the passage manifestly written in the time and tone of Prosper of Aquitaine, secretary to Pope Leo the Great in the mid-5th century, who was supportive of the missions of Germanus of Auxerre and Palladius. Duchesne dated the entry a little later, Boniface II’s pontificate around 530, and Mommsen to the early 7th century. Only the latter would support the conjecture that it aimed to support the Gregorian mission to the Anglo-Saxons led by Augustine of Canterbury, who encountered great difficulty with the native British Christians, as at the Synod of Chester. Indeed, the Celtic Christians invoked the antiquity of their church generally to avoid submission to Canterbury until the Norman conquest, and more recently, since the English Reformation and the reign of Elizabeth I, it has been used to legitimate the Church of England as contrasted with the rule of Rome (there are references to the first-century kings of Britain in the coronation liturgy and the royal genealogy). From the eighth to the eleventh centuries, no arguments invoking the mission to Lucius appear to have been made by either side during the synods between the Welsh and Saxon bishops.

https://i2.wp.com/spitalfieldslife.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/IMG_5561.jpg?w=600&ssl=1

Lucius is first mentioned in a 6th-century version of the Liber Pontificalis, which says that he sent a letter to Pope Eleutherius asking to be made a Christian. The story became widespread after it was repeated in the 8th century by Bede, who added the detail that after Eleutherius granted Lucius’ request, the Britons followed their king in conversion and maintained the Christian faith until the Diocletianic Persecution of 303. Bede was the first authentic British source to make mention of this story and he seems to have taken it, not from native texts or traditions, but from The Book of the Popes. Subsequently, it appeared in the 9th-century History of the Britons traditionally credited to Nennius: The account relates that a mission from the pope baptised Lucius, the Britannic king, with all the petty kings of the whole Britannic people. ‘Petty’ is not a slur here, but an indication of the supremacy of Lucius as ‘Braetwalda’ or ‘High King’ of the Britons. In the twelfth century, more details began to be added to the story. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s mid-twelfth-century pseudohistorical History of the Kings of Britain goes into great detail concerning Lucius. Geoffrey of Monmouth was born in the early years of the century, studied at Oxford, and was probably a Benedictine monk. Archdeacon of Llandaff, circa 1140, and Bishop of St Asaph in 1152-54, when he died. In his History, Geoffrey names the pope’s envoys to him as Fagan and Dyfan:

… being minded that his ending should surpass his beginning, he dispatched his letters unto Pope Elutherius, beseeching that from him he might receive Christianity. For the miracles that were wrought by the young recruits of Christ’s army in divers lands had lifted all clouds from his mind, and panting with love of the true faith, his pious petition was allowed to take effect, forasmuch as the blessed Pontiff, finding that his devotion was such, sent unto him two most religious doctors, Pagan and Duvian who, preaching unto him the Incarnation of the Word of God, did wash him in holy baptism and converted him unto Christ.

George F. Jowett, in his 1961 book, The Drama of the Lost Disciples, claimed that St. Timotheus journeyed from Rome to Winchester to baptise Lucius, at the same time consecrating him as Defender of the Faith, in AD 137. According to his genealogy, Lucius was the son of Coel (of ‘Old King Coal’ fame), as also stated by Geoffrey, and could trace his ancestry back to Llyr (‘Lear’). Welsh sources variously give his birthplace as Llanilid in present-day Glamorgan or Ewys in Monmouthshire. Others refer to Colchester. His native name was apparently Lleurug Mawr, meaning ‘Great Light’. The Romans Latinised his name as ‘Lucius’, from the Latin ‘Lux’, carrying the same implication as the Celtic to the Romans, ‘the Great Luminary’.

Jowett claims that Lucius made his royal seat at Caer Winton, romanised to Winchester. The city was founded by the British ‘king’, Dunwal Molmutius, one of the legendary ‘three wise British kings’, who made Winchester his royal capital in circa 500 BC, instead of the older capital of London (‘Llundain’ in Welsh). It was also known as the ‘White City’, due to the chalk walls with which he surrounded the city. Even when London was re-established as the royal capital of Britain, Winchester continued to be known as ‘the Royal City’ and, in the time of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, it was the royal capital of Wessex. William the Conqueror refused to consider his coronation at Westminster valid until he had been crowned a second time at Winchester, no doubt as a cover for his usurpation of the Royal House of Wessex, which Edward the Confessor had named as his successors so that William could justify his rightful claim to the British throne, where all true British Kings had been crowned. Geoffrey of Monmouth claimed that Lucius’ baptism had a major effect on his subjects and man others among the Britons leading to mass conversion to the Christian faith and its establishment as a national faith:

Straightway the peoples of all the nations around came running together to follow the King’s example, and cleansed in the same holy laver, were made partakers of the kingdom of Heaven. The blessed doctors, therefore, when they had purged away the paganism of well-nigh the whole island, dedicated the temples that had been founded in honour of very many gods unto the One God and unto His saints, and filled them with divers companies of ordained religious. … there did they set up bishops and archbishops … in the three noblest cities, in London, … in York and in Caerleon … from these three was superstition purged away, and the eight-and-twenty bishops, with their several dioceses, were subordinated unto them.

At last, when everything had been thus ordained new, the prelates returned to Rome and besought the most blessed Pope to confirm the ordinances they had made. And when the confirmation had been duly granted, they returned into Britain with a passing great company of others, by the teaching of whom the nation of the British was in a brief space established in the Christian faith. …

Meanwhile King Lucius the Glorious, when he saw how the worship of the true faith had been magnified in his kingdom, did rejoice with exceeding great joy, and converting the revenues and lands which formerly did belong unto the temples of idols unto a better use, did by grant allow them to be still held by the churches of the faithful. And for that it seemed him he ought to show them yet greater honour, he did increase them with broader fields and fair dwelling-houses and confirmed their liberties by privileges of all kinds.

Besides Geoffrey of Monmouth, there is a wealth of material extolling the exemplary life of Good King Lucius, among which are the writings of Bede, Nennius, Elfan, Cressy, William of Malmesbury, Ussher (who states that he had consulted twenty-three works on Lucius: Rees, Baronius, the Welsh Triads, The Mabinogion, Achai Sant Prydain, and many other reliable works, all of which pay tribute to the Christian monarch). Another twelfth-century Welsh source, The Book of Llandaff by Alford placed the court of Lucius in southern Wales and names his emissaries to the pope as Elfan and Medwy. According to Geoffrey, Lucius died in AD 156, and was buried in ‘the church of the first see’. However, earlier sources suggest that this date must have been later, towards the end of the second century, if this mission occured during the pontificate of Eleutherius. In A Guide to the Cathedral, compiled at Gloucester in 1867, the Rev. H. Haines wrote:

King Lucius was baptised on May 28, A.D. 137 and died on December 3, 201. His feast has been kept on both these days, but the latter is now universal.

Many researchers and writers seem to have confused the date of his baptism with his date of birth. Some sources suggest that this was around AD 120, possibly as early as 117. He was clearly an adult at the time of his baptism, which took place after his conversion to Christianity. There is also a great deal of variance concerning the date of his death, but more than one source has 181 or 201, so we have no reason to doubt Rev. Haines’ account. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s account is clearly wrong. In fact, Jowett refers to the year 156 as marking the date when, at the ‘National Council’ at Winchester, Lucius ‘established Christianity as the National Faith of Britain’. Jowett quotes the British Triads in support of this assertion:

King Lucius was the first in the Isle of Britain who bestowed the privilege of country and nation and judgement and validity of oath upon those who should be of the faith of Christ.

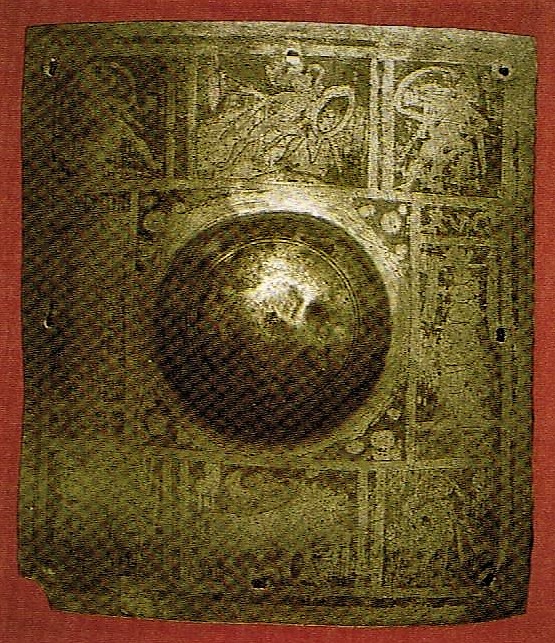

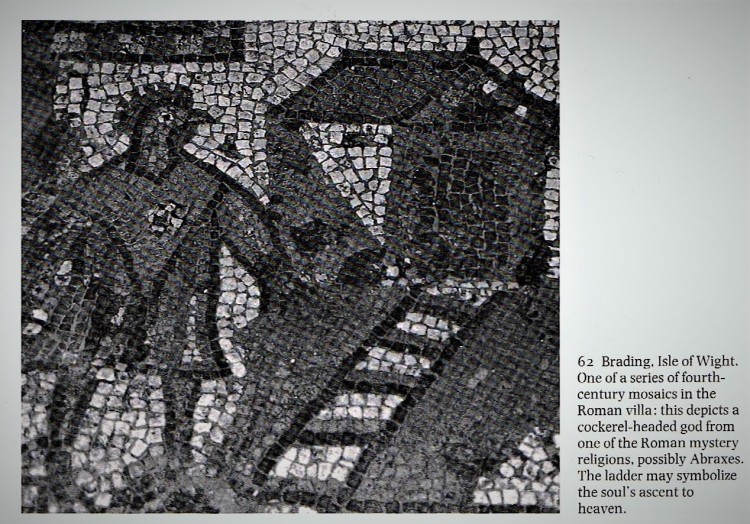

However, his suggestion that this somehow the establishment of Christianity by Act of Parliament is anachronistic and without foundation in the source material. Neither is it likely that the emissaries of the ‘Pope’ had purged away the paganism of well-nigh the whole island as Geoffrey of Monmouth suggested. As the relics in villas and temples tell us, like the ones pictured here, pagan beliefs and practices were alive and well, and widespread, long into the fourth century. It is difficult to believe that this was due solely to the restoration of pagan icons following the persecution of Christianity under Diocletian. Second and third century finds near the site of the Temple of Mithras at Walbrook in London, which are of Italian origin, suggest that both pagan religion and commercial life in London remained vibrant and wealthy, with the local demand for expensive works depicting pagan deities increasing.

This evidence belies the statement that ‘superstition’ was ‘purged away’ by Christian missionaries. The more inward spiritual needs of people were met by the mystery religions of the classical world, the most notable of which were those of Cybele, Isis and Mithras. It would seem that there was a temple of the Egyptian goddess Isis in London and a triangular temple at Verulamium, from the furnishings found during excavations, has been identified as a shrine of the mother goddess Cybele, the object of wild and ecstatic rites. Her priests would castrate themselves in her honour. We have much fuller evidence of the worship of Mithras, partly because his cult was particularly popular among Roman soldiers. Mithraism, which had its origins among the Persian religion of Zoroastrianism, was a Sun religion imported into the empire in the first century BC. Depicted as a beautiful young man wearing a Phrygian cap, Mithras was a god of the Zoroastrian pantheon and was frequently addressed as Sol Invictus, the unconquered Sun. He was supposed to have been born from a rock and in the course of his adventures he seized and sacrificed a huge bull by which he won salvation for mankind. This bull sacrifice is frequently depicted in art, notably in the sculptures found associated with the Temple of Mithras, the Mithraeum, discovered in London in 1954 and moved to a nearby site in the open air to enable it to be reconstructed and preserved.

Once the Mithraeum stood close to the Walbrook, a stream held sacred spring held sacred by the Celts who would fling sacrificial heads into its waters. Now its mysteries are bared to the vulgar and the curious where once masked devotees wearing the heads of birds and beasts would strike awe into the hearts of initiates. Another Mithraeum exists at Carrawburgh on Hadrian’s Wall, close to the sacred spring of the Celtic nymph Coventina. This Mithraeum was founded soon after AD 205 and it was probably desecrated by Christians in the early fourth century after the proclamation by the British-born Emperor Constantine of Christianity as the state religion of the Empire. The stern demands of the cult in terms of physical and moral courage and its stages of initiation through seven grades won by ordeals and tests would have won the adherence of many soldiers. The ordeal pit in which devotees were subjected to extremes of heat and cold may still be seen at Carrawburgh. Mithraism was a cult for men alone. It was looked on with favour during the later years of empire because its adherents never refused the sacrifices and oaths of the official state religion. This was what the Christians insisted on doing, inviting martyrdom and terrible sufferings by their recusancy.

For centuries the legend of Lucius, this “first Christian king” was widely believed, especially in Britain, where it was considered an accurate account of Christianity among the early Britons. During the English Reformation, the Lucius story was used in polemics by both Catholics and Protestants; Catholics considered it evidence of papal supremacy from a very early date, while Protestants used it to bolster claims of the primacy of a British national church founded by the crown. Certainly, Lucius’ declaration was well-received by Christians in other lands. Sabellius, writing in AD 250, shows how it was acknowledged elsewhere beyond the shores of Britain:

Christianity was privately confessed elsewhere, but the first nation that proclaimed it as their religion, and called itself Christian, after the name of Christ, was Britain.

Gilbert Génébrard was a sixteenth-century French Benedictine exegete and Orientalist. He declared:

The glory of Britain consists not only in this, that she was the first country which in a national capacity publicly professed herself Christian, but that she made this confession when the Roman Empire itself was pagan and a cruel persecutor of Christianity.

This statement is important, proving the invalidity of the claim by the Roman Catholic Church, centuries later, that the founding of a ‘national’ church in Britain was brought around by ‘Pope’ Eleutherius of Rome. The fact is that no allusion was made to this claim by the church at Rome until the Augustinian Mission in 597, over four hundred years after Lucius’ declaration. Then, Augustine was angered by the British bishops telling him:

We have nothing to do with Rome. We know nothing of the Bishop of Rome in his new character of the Pope. We are the British Church, the Archbishop of which is accountable to God alone, having no superior on earth.

Writing almost a millenium later, the Elizabethan Francis Bacon used this rejection of Augustine’s authority to justify the English Reformation, writing in his Government of England:

The Britons told Augustine they would not be subject to him, nor let him pervent the ancient laws of their Church. This was their resolution, and they were as good as their word, for they maintained the liberty of their Church five hundred years after this time, and were the last of all the churches of Europe that gave up their power to the Roman Beast, and in the person of Henry VIII, that came of their blood by Owen Tudor, the first that took that power away again.

In this way, the old British legend of Lucius became one of the popular myths of the Tudor state and part of its Protestant propaganda during and following the break with Rome. On the other hand, it did have certain facts to support it. Gregory I was not appointed Pope. That title, equivalent to ‘Universal Bishop’, was first given by Emperor Phocas in AD 610 to Boniface III, as a result of the division of the Empire and the Church into Eastern, based on Constantinople, and Western, on Rome. During the alliance with the Empire, however, the heads of the British church were never anything but bishops, and they inherited their apostolic succession from the original apostles of Christ. Yet in later years, it became a habit of many Roman church writers to refer retrospectively to all the former ‘bishops of Rome’ as ‘Popes’, including Peter, Paul and Linus. By making the spurious claim that Lucius had pleaded with the Bishop of Rome, ‘Pope’ Eleutherius, to send his representatives to Britain to convert him and proclaim Britain Christian, the Roman church was able to claim the British church as its own.

In AD 170, Lucius founded his church at Winchester, which later became Winchester Cathedral. In AD 183, he sent his two emissaries, Medwy and Elfan, to Rome to obtain the permission of Bishop Eleutheris for the return to Britain of some of the British missionaries aiding him in his evangelising role within other parts of the Roman Empire in order that he, Lucius, could better carry out his evangelisation in Britain. In the same year, the missionaries returned to Britain. In his letter to King Lucius, Bishop Eleutherus plainly shows that he is aware that Lucius possessed all the necessary knowledge of the Christian teaching beforehand and needed no advice from him and that he had no part in evangelising the whole of Britain. As Geoffrey of Monmouth testified, Lucius also established the three famous Archbishoprics of London, York and Caerleon on Usk. In AD 179 he is also reputed to have built St Peter’s on Cornhill. The church is often referred to as the finest Christian Church ever erected in London. During the ensuing centuries, this church was enlarged but was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666, which almost completely levelled the ancient city. The tablet telling the history of this great church, embedded in the original walls, survived the Great Fire and has since been preserved in the vestry. It bears the following inscription:

Bee it knowne to all men that the yeare of our Lord God 179, Lucius, the first Christian King of the land, then called Britaine, founded the first church in London, that is to say, the church of St Peter upon Cornhill. And hee founded there an Archbishops See and made the church the metropolitaine andchief church of the kingdome; and so indured the space of four hundred years unto the coming of St Austin the Apostle of England, the which was sent into the land by St. Gregoire, the doctor of the church in the time of King Ethelbert. … And in the yeare of our Lord God 124, Lucius was crowned king and the yeares of his reign were seventy-seven yeares.

Among other churches founded by Lucius were those at Llandaff and St. Mellons in Cardiff, still referred to as Lucius’ church. He is also said to have founded the church of St. Mary de Lode in the city of Gloucester, where he was interred. Lucius was also the first British monarch to mint his coins displaying the sign of the Cross on one side and on the other side his name, ‘Luc’: In the coin collection held by the British Museum there are two coins which bearing these motifs. From Claudius to the reign of the Emperor Hadrian, no coins with the Roman emperors’ motifs have been found in Britain. But from Hadrian onwards, complete sets of Roman coins are found. This indicates the shift from hostility to compromise in the attitudes of Britons towards the Roman ‘occupation’ which had taken place by the 140s. The coins of the British kings were all minted at Colchester, confirming its continuing importance as a centre for British royalty well into the second century, certainly more important than London at this time.

King Lucius was first buried where he died, in Gloucester, but was later reinterred at St. Peter’s on Cornhill. Much later, his remains were again moved to Gloucester, where they were placed in the choir of the Franciscan church by the Earls of Berkley and Clifford, founded by the two families. Bede, writing in AD 740, sums up the picture of Lucius in a few brief words, but with his characteristic eloquence:

The Britons preserved the faith which they had nationally received under King Lucius uncorrupted and entire, and continued in peace and tranquility until the time of the Emperor Diocletian.

Bede: Book I, chapter 4.

We must conclude, therefore, that the earliest sign of Christianity coming to Britain is this record by Bede. The earliest archaeological evidence comes from Manchester, dated to later in the second century. The savage Diocletian persecution, which came to Britain at the very end of the following century, broke the peace and produced the conquering Constantine. The great peace which had settled over the Island, beginning with Agricola’s treaty in AD 86, continued for a period of two hundred years. There is no mention of any major British-Roman military conflict during the second and third centuries until the year 287, which I shall return to in my next article in this series.

The Legends of the ‘Proto-Martyr’, St Alban of Verulamium:

The Diocletian persecution is described as the tenth Christian persecution, beginning with the Claudian Edict of AD 42. Until recently, it was generally thought that St Alban suffered under this persecution and was martyred in 303, but it is now thought that his martyrdom took place during the reign of Emperor Septimus Severus on 22 June 209. St Alban (Latin: Albanus) is venerated as the first recorded British Christian martyr, for which reason he is considered to be the British protomartyr. Along with fellow Saints Julius and Aaron, Alban is one of three named martyrs recorded at an early date from Roman Britain (“Amphibalus” was the name given much later to the priest he was said to have been protecting).

Alban is traditionally believed to have been beheaded in the Verulamium (St Alban’s) sometime during the 3rd or 4th century, and his cult has been celebrated there since ancient times. But little is known about his religious affiliations, socioeconomic status, or citizenship. According to the most elaborate version of the tale found in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, in the 3rd or 4th century, Christians began to suffer “cruel persecution”, and Alban was living as a citizen in the important municipium of Verulamium. However, Gildas says he crossed the Thames before his martyrdom, so some authors place his residence and the site of his martyrdom in or near London. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle lists the year of this as 283, but Bede places it in 305, … when the cruel Emperors first published their edicts against the Christians. In other words, it was sometime after the publication of the edicts by Eastern Roman Emperor Diocletian in 303 and before the proclamation of toleration in the Edict of Milan by co-ruling Roman Emperors Constantine I and Licinius, in 313. In stating this, Bede was probably following Gildas.

There is little differentiation in the story of his martyrdom, however. According to the version told by Bede, Alban was a pagan who sheltered a Christian priest from persecution. He was converted by the priest and when soldiers came to seize the priest, Alban, wearing the priest’s cloak, gave himself up instead of his guest. Led before the magistrate, he was asked to make the customary sacrifices and refused. “What is your family and your race?” demanded the judge. “How does my family concern you?” replied Alban: “if you wish to know the truth about my religion, know that I am a Christian, and am bound by the laws of Christ.” “I demand to know your name”, insisted the judge, “tell me at once”. “My parents named me Alban”, he answered., “and I worship and adore the living and true God, who created all things.” The infuriated magistrate ordered him to be flogged and then, because Alban still resisted, beheaded. Led to execution outside the to the hill where his abbey now stands, Alban came to the river Ver and which could not be crossed because of the crowd gathered on the bridge. At his prayer, the waters of the Ver parted and Alban and the soldiers crossed over and up the hill. The soldier appointed to execute him threw away his sword and begged to join him in martyrdom. At the summit of the hill, Alban prayed for water and a spring bubbled up. Then he was beheaded and the soldier who had refused to execute him was beheaded as well. As for the substitute executioner, his eyes dropped out of his head onto the ground. In later legends, Alban’s head rolled downhill after his execution, and a well sprang up where it stopped. Bede writes that the magistrate was so astounded by these miracles that he called a halt to the persecutions and was himself converted.

British historian John Morris suggested the earlier date for Alban’s martyrdom on the basis of claims in the Turin version of the Passio Albani, unknown to Bede, which states,

Alban received a fugitive cleric and put on his garment and his cloak (habitu et Caracalla) that he was wearing and delivered himself up to be killed instead of the priest… and was delivered immediately to the evil Caesar Severus.

According to Morris, Gildas knew the source but mistranslated the name “Severus” as an adjective, wrongly identifying the emperor as Diocletian. Bede accepted the identification as fact and dates St Alban’s martyrdom to this later period. As Morris points out, Diocletian reigned only in the East and would not have been involved in British affairs in 304; Emperor Severus, however, was in Britain from 208 to 211. Morris thus dates Alban’s death to 209. However, the mention of Severus in the Turin version has been shown to be an interpolation into an original text, which mentioned only a iudex or ‘judge’.

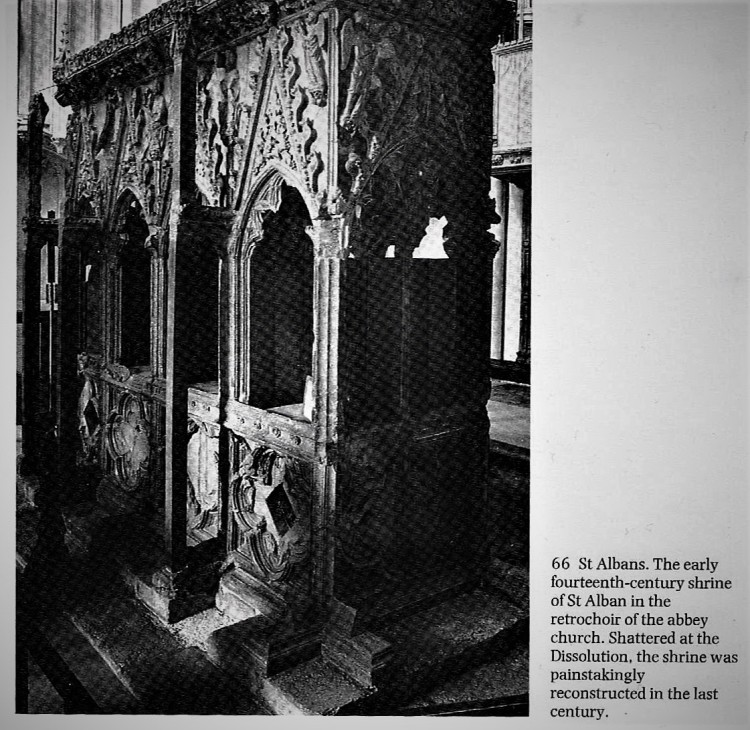

Alban’s fame spread abroad and lasted into the Dark Ages. His body was rediscovered in the eighth century by the Saxon King Offa who richly endowed the abbey. The present great church, the second-longest in England, was built by the first Norman abbot, Paul of Caen, using Roman bricks from the ruins of Verulamium. The site of Alban’s shrine behind the high altar is one of the most charged of all the holy places of early British Christianity. As William Anderson remarks,

The air sings with the words of Christ; “Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends”, and about you rises the the evidence of the civilizing force that derives from true sacrifice and fructifies throughout the succeeding centuries the resources of art.

Sources:

David Shotter, et.al. (2001), The Penguin Atlas of British & Irish History. London: Penguin Books.

Philip Parker (2017), History of Britain in Maps. Glasgow: HarperCollins.

David Smurthwaite (1984), The Ordnance Survey Complete Guide to the Battlefields of Britain. Exeter: Webb & Bower.

William Anderson, Clive Hicks (1983), Holy Places of the British Isles: A guide to the legendary and sacred sites. London: Ebury Press.

George F. Jowett (1961), The Drama of the Lost Disciples. London: Covenant Publishing.

Ernest Rhys (ed.) (1912), Histories of the Kings Of Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth (translated by Sebastian Evans). London: Dent & Sons.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucius_of_Britain

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Alban